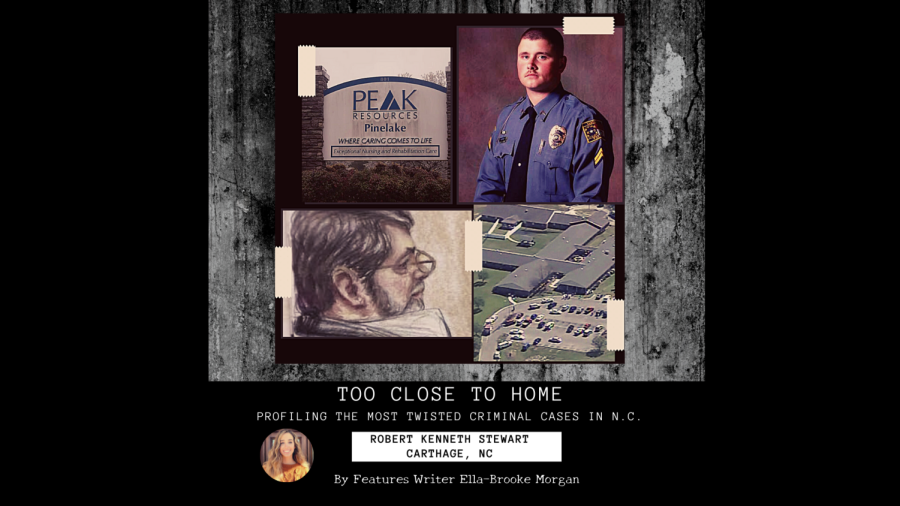

Too Close To Home: Robert Kenneth Stewart – Carthage, Moore County

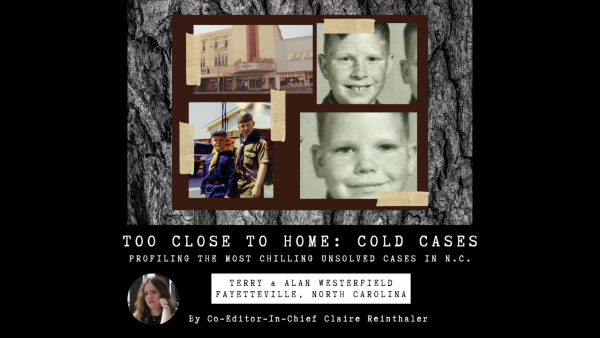

Clockwise from top left: Peak Resources Pinelake, hero officer Justin Garner, Pinelake after the shooting, and an artist’s sketch of Stewart during the trial.

April 6, 2022

(Clemmons to Carthage – 1 hour and 30 minutes away)

Profiling the most twisted criminal cases in North Carolina.

Trigger warning: graphic content – mass violence, substance abuse, discussions of mental health struggles

Eight seconds was all it took for a gruff painter to murder seven nursing home residents and one terrified caretaker 13 years ago on March 29, 2009.

Robert Kenneth Stewart, then 45, had lost everything. He had been out of work for over a year, he could hardly make ends meet, and his wife Wanda Neal had left him. Neal’s marriage to Stewart in 1983, when she was 17-years-old, had only lasted three years, but after decades had passed, they wanted to give it another try. Stewart’s 15-year marriage to Sue Griffin during Stewart and Neal’s separation ended in divorce, with Stewart and Neal attempting to rekindle their relationship and remarrying in 2002.

Their time apart wasn’t enough to improve things between them, though; Neal’s mother attested to the convulsive fits of drunken fury Stewart would have, saying, “He had a rage, it would just explode over everything. He would be good and then something would just set him off.” Stewart’s promises of “I’ll change,” “I’ll quit drinking,” and “I’ll treat you right” proved to be empty. Towards the end of their relationship, Stewart had grown so possessive of Neal that he did not allow her to go anywhere alone. At one point, Stewart put a gun to Neal’s head and threatened to end her life. After their separation, she was the subject of countless phone calls made by Stewart to Neal’s family at 2 or 3 a.m. Stewart would claim there was an “emergency” and that he needed to see Neal and her parents immediately.

Stewart’s financial troubles were ample too. After losing his business in house painting, Stewart was forced to file for bankruptcy twice. Although Stewart’s prospects improved once he began to receive disability benefits for a prior injury, the compensation wasn’t enough, and Stewart fell into a deep depression.

According to locals, Stewart was a coward, and he sought an outlet in which he could disrespect others without consequences. Tim Allred, a friend from the hunting club Stewart had been a member of, spoke of this.

“Big talk, no show. You know what I mean? Just like he walked in on that rest home up there. He went in where he knew nobody could whip him. That was the cowardice in him.”

Things came to an ugly head after Neal finally left Stewart, who had written several letters and notes in the days before the shooting that pointed to premeditation. Neal was an employee at Peak Resources Pinelake, formerly known as Pinelake Health and Rehab, where she attended to patients in the Alzheimer’s ward of the facility.

Sunday, March 29, 2009 came; the morning was windy and cool. Stewart rose early that day, making the 20-minute trip from his home in Robbins to the nursing home in Carthage where Neal worked as a nurse.

The first shot, a sinister harbinger, rang out in the parking lot at 10 a.m. Stewart had brought a .22 caliber hunting rifle with him like those he used to fire at empty barrels in his yard, and he fired into the window of Wanda Neal’s empty car. Michael Cotten, an innocent bystander, was shot in the shoulder shortly after that, but managed to call 911 as he ran into the care center seeking safety. Stewart used that moment to switch weapons, and he was ready for action. He had a 12-gauge-pump shotgun in his hand, a 357-caliber revolver and semi-automatic pistol on his waist.

Stewart’s 380-pound frame dominated the main hall of the nursing home as he began to fire randomly at the elderly residents. Stewart killed eight people almost instantaneously. Ninety-eight-year-old Louise DeKler, the oldest of the victims, remains the oldest person to be murdered in a mass shooting. The only non-resident slaughtered was 38-year-old Jerry Avant Jr., a U.S. Coast Guard officer-turned-nurse, who was believed to have died attempting to lead the other elderly people to safety. He was shot at close range. His fiancée Jill DeGarmo, who also worked at Pinelake, found him “laying on the floor bleeding.” Avant later succumbed to his injuries. The only responding officer at the scene, Justin Garner, remembers witnessing the carnage and how other residents were walking around as if it were “just another morning,” disconnected from the gravity of what just happened. Garner, who was 25-years-old at the time, did not hesitate or wait for backup; he pursued Stewart as Stewart pursued the password-protected Alzheimer’s ward where Neal was hiding in a bathroom.

A standoff took place as Garner found Stewart reloading his shotgun; the shooter was “hard to miss.” Garner yelled at the man to drop his weapon, but Stewart leveled it. Garner brought out his service pistol. Shooting one another nearly in unison, bullets landed themselves in Garner’s leg and foot and Stewart’s chest. Stewart crumpled and collapsed on the blood-smeared ground, begging Garner to kill him. Later on, Garner’s heroic actions would be recognized by national media and police organizations.

The trial was nearly unbearable for the victims’ families, who punctuated the otherwise-still courtroom with anguished sobs, as Stewart appeared blank throughout the proceedings. His defense team argued that Stewart’s actions were a side-effect of “automatism,” or a sleepwalk-like state induced by a dangerous mixture of Ambien, Xanax, and Lexapro. The prosecution quickly countered this with examples of complex plans carried out by Stewart, such as the gathering of multiple firearms; they also mentioned Stewart’s writings.

The jurors were quickly given the nickname “The Smoking Jurors.” The group of 12 “outsiders” became notorious for requesting several smoke breaks under the sheriff’s supervision. They lit up multiple times as deliberations passed for 10 hours. The group returned to the jury box, and the verdict was in: Stewart was found guilty of eight counts of second-degree murder and sentenced to 179 years in prison. It wasn’t enough for some victims’ families, who preferred Stewart to be executed, just as he had executed their loved ones. Neal remained physically unscathed but she suffered significant emotional damage, even attempting suicide prior to the trial.

Stewart, now 58, sitting behind bars at the medium-security Caswell Correctional Center in Yanceyville. Over the years, Stewart has written several letters from prison, all of which are added to his thick case file. He has also initiated lawsuits and started petitions for habeas corpus on frivolous grounds. It’s unlikely they will affect Stewart’s legal situation, as in prison, he has already been cited for fighting and possession of a dangerous weapon.

Garner, who now works for the Highway Patrol, has been used as an example of handling mass shootings and has even spoken to classes in Basic Law Enforcement Training. He set a precedent across the nation for immediate and decisive action. His recognition by the House of Representatives and the American Police Hall of Fame only resulted from what “any self-respecting police officer would do.” He says his struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder in the years following the massacre would have been intensified by guilt if he had not done anything.

The writings of his imprisoned, antithetical counterpart are now puzzling when re-examined, raising more questions about the incident and what led to it. An entry Stewart logged in his journal on March 21 details his thoughts of suicide. “I thought about taking a lot of people with me, but I don’t care to do that,” he wrote.