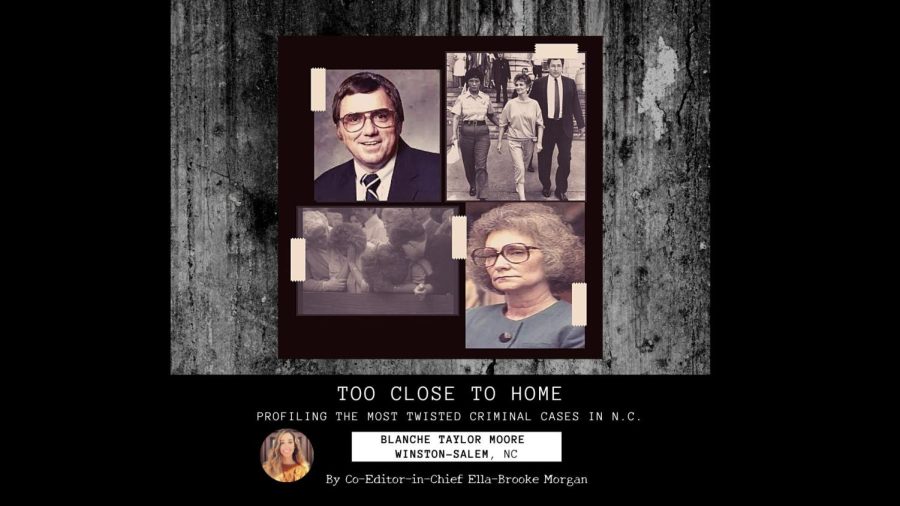

Too Close To Home: Blanche Taylor Moore – Winston-Salem

Clockwise from top left: Blanche’s ill-fated husband, Rev. Dwight Moore, Blanche cooly faces the press while leaving her arraignment, Blanche’s grandmotherly demeanor during her trial, the Kiser women weep as Blanche is found guilty.

March 20, 2023

(West Forsyth High School to Winston-Salem – 15 minutes)

Profiling the most twisted criminal cases in North Carolina.

Trigger warning: Discussions of sexual and domestic abuse, religious trauma

The Bible verse Ephesians 6:4 NIV reads, “Fathers, do not exasperate your children; instead, bring them up in the training and instruction of the Lord.” Blanche Taylor Moore’s minister father, Parker D. Kiser, should have known this well. But after selling Blanche into prostitution beginning when she was twelve years old, the trauma he inflicted on her would bring him, along with several other men, to their deathbeds by way of arsenic poisoning. The cross she bore would send her to death row, where she remains.

Born Blanche Kiser in Concord on Feb. 17, 1933, to Parker D. Kiser, known as “P.D.,” and “Flonnie” Kiser, Blanche’s childhood as the daughter of a southern Baptist “fire-and-brimstone” preacher was far from pious. P.D.’s persona as a righteous man was a facade for the cruelty he hid behind closed doors; when he wasn’t in the sanctuary or working at the local mill, her alcoholic father forced Blanche into sex work to pay off gambling debts. The fifth out of seven kids, Blanche was helpless as P.D. physically beat her, her siblings and her mother.

The abuse’s effect on Blanche cannot be understated, as evidenced by the habits she would retain in her adult life; this is a common theme throughout Jim Schutze’s book “Preacher’s Girl: The Life and Crimes of Blanche Taylor Moore,” where he writes of Blanche’s tendency to seamlessly switch from reciting Bible verses to discussing sexually explicit topics in a manner that would shock and disturb her coworkers.

When Blanche turned 19, she met and married a 24-year-old veteran and furniture restorer named James Taylor, seeing the relationship as an “escape” from her current home life. She gave birth to two of his children, and a year after her oldest daughter arrived in 1953, she began working at a Kroger grocery store in Burlington. Blanche was promoted to head cashier in 1959 and began an affair with the store’s assistant manager, Raymond Reid, in 1965. Her marriage with Taylor had soured and escalated into arguments reminiscent of those between P.D. and Flonnie Kiser. In 1966, Blanche attempted to make peace with her father, whose health was sharply declining. When he passed away, his cause of death was ruled to be a “heart attack.”

Taylor, who, in 1968, also suffered a heart attack, was quickly moved to change his ways and rectify his past behaviors towards his wife and kids. It wasn’t enough for Blanche, though. She had already emotionally distanced herself from Taylor; Reid was her new fixation, and fortunately, he left his family to be with her. 1971 rolled around, and Taylor began experiencing symptoms of a curious illness–diarrhea, a sore throat, hair loss and painful blisters. He passed on Oct. 2 after coping with sickness for a month. Blanche was now free from all connections to the Taylor family, her mother-in-law, Isla, preceding Taylor in death by a year.

Blanche and Reid were now public with their courtship, but again, Blanche was distracted by another man. Having moved up Kroger’s chain of command in search of a new partner, she trapped Robert Hutton, Kroger’s regional manager for the Piedmont Triad area, in her clutches. Once the relationship became risky, and Blanche was strapped for cash after purchasing a new home, she filed a sexual harassment lawsuit targeting Hutton and Kroger in 1985. A PR nightmare, Hutton was forced to resign from Kroger; Blanche received $275,000 in 1987, claiming that the ordeal had damaged her to the extent of being unable to have social contact with a male.

Blanche’s next attraction, the newly-divorced Rev. Dwight Moore, would reignite her faith in God. Approaching him on Easter Sunday of 1985, the pair’s romance blossomed. Simultaneously, Reid’s health deteriorated, and he was hospitalized for severe shingles, finally dying in Oct. of 1986. Blanche saw her clearing; she and Moore wed in April of 1989. Just days following their honeymoon, which had been foreshadowed by a bout of vomiting on Moore’s part, Blanche’s new husband collapsed after eating a pastry. Blanche insisted on driving Moore back home to Burlington, passing her invalid partner between North Carolina Memorial and Alamance Hospitals, Moore’s condition worsening after each meal he ate.

Blanche’s mysterious strokes of “poor luck” would soon make sense, and her deceit would come crumbling when toxicology tests were run on Moore; it was discovered that his organs contained twenty-three times the lethal amount of arsenic. Miraculously, sheer will and a history of good health before he met Blanche sustained him, and he survived. In an interview in 2010, Moore stated he still has no feeling in some of his limbs.

Her former lover Reid’s body was exhumed, or recovered from its burial plot, and found to contain arsenic. The same result appeared for James Taylor. Prosecutors now had the evidence and financial statements to support their belief that Blanche Taylor Moore, who was seen as a devout church wife, had murdered the men in her life in cold blood for a quick buck.

After being arrested for the first-degree murder of Raymond Reid, Blanche was tried in Winston-Salem in Oct. of 1990. Sporting tortoiseshell glasses and blouses that could’ve belonged to a typical religious grandmother, Blanche consistently denied any crime, alternating between teariness and stoicism when testifying. Her assertions weren’t any good, though, because 53 witnesses came out of the woodwork to recount Blanche’s daily trips to the hospital with food for Reid. Blanche was found guilty on Nov. 14–the jury deliberated for three days–and would sentence her to death. Because of this, prosecutors felt it was futile to add charges for the other assumed victims (P.D. Kiser and Isla Taylor) to a woman already condemned to death row.

Blanche Taylor Moore, or the “Black Widow,” is the oldest woman in the country waiting to be executed, but reoccurring cancers will likely take her life first. Allegedly, she spends her time writing poetry and has undergone multiple rounds of chemotherapy.

Today, in a modest cell in the North Carolina Correctional Institution for Women, Blanche Taylor Moore does not have a name of her own, or even the name of a past husband or lover. She is not known as anything; she is simply prisoner #0288088.