What good is voting when nothing ever gets done?

February 15, 2022

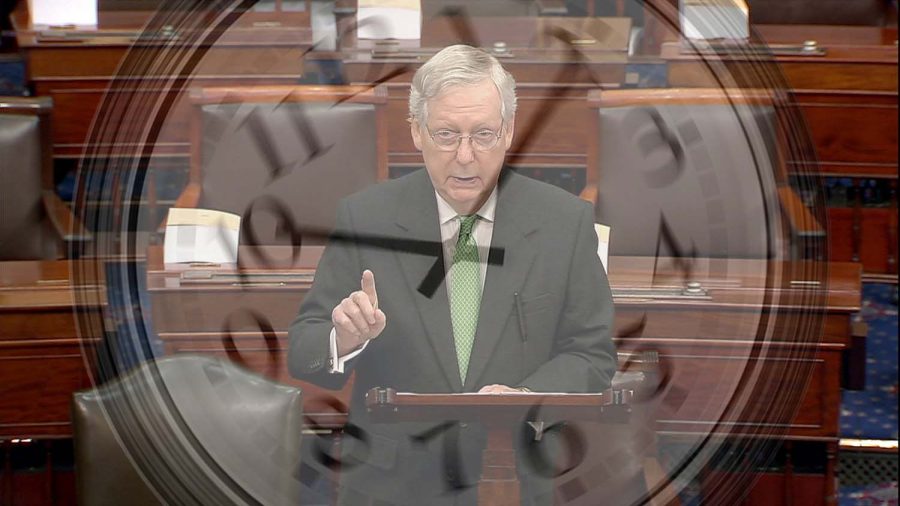

Spending time in the weeds of heady political jargon, as I have been a lot recently, has given me a newfound appreciation for simplicity. The Senate is broken. The filibuster is to blame.

Just look at the news. The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act passed the House of Representatives in August of last year. Yet, when it met the Senate, there it sat for months, and months, and months. The Democratic majority in the Senate supports the bill, they easily have the 51 votes needed to pass it. Republicans know this, which is why they are delaying when the bill is called to the floor – a tactic known as a filibuster.

An endless filibuster has ground the Senate’s legislative process to maddening halt. Any bit of partisan legislation, the qualifications for “partisan” shrinking by the day, is silently blocked into oblivion by the minority party. None of the dissenters even have to take the Senate floor, much less maintain it to keep the filibuster going.

The filibuster was born of a loophole, and its unrecognizable transformation is the product of another loophole. It is evident that the Senate’s amendments have come with a lack of foresight; animosity between parties has been continuous, but our current Senate takes this opposition to its furthest logical conclusion: to absolute self-destruction. Gridlock. Stalemate. Friends, welcome to the era of the silent filibuster.

South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond walked into the Senate hall with an exuberant, sickening confidence. His lips flirted with a smirk as he sized up the floor in front of him. He was there to deliver a filibuster, what would become known as the filibuster, on the Civil Rights Act of 1957: a bill that sought to protect the right for African Americans to vote. He took the floor at 8:54 p.m. and resigned it at 9:12 p.m. the next day. Cots were carried into the hall; the majority party’s members slept during Thurmond’s speech.

After 24 hours, Thurmond finally resigned the floor. His stunt was not supported by any of the other members of his party, so the Civil Rights Act passed without a hitch two hours later. But if this were a coordinated bid, the southern Democrats could have passed the floor to one another and easily stalled the bill for at least another month’s worth of meandering speeches. And make no mistake, they did do this. They did it with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, clearly demonstrating the filibuster’s vile use as a deterrent to Civil Rights legislation, and a tool primarily used by warped, idiotic bigots. They were allowed to postpone these monumental bills because of the nearly nonexistent restrictions on Senate debate at the time – the “cloture vote” was the only way interrupt debate, and its requiring approval from 2/3 of the Senate body was a sure guarantee that it would rarely be used.

Southern opposition to Civil Rights legislation made many similarly dramatic scenes using the Senate’s filibuster, and coming out of the 20 years that saw the filibuster’s frequent deployment, Senators in the 1970s wanted to be sure that such indulgent wastes of time wouldn’t happen again. They created the “two track system,” which allowed for multiple bills to be pending on the Senate floor at once. This meant that if a Senator objected to the consideration of a bill or threatened to filibuster, that another bill could be brought to the floor instead. In addition, the system mandated that all threats to filibuster were equal in weight to actual filibusters, and must be responded to by a cloture vote (changed from 2/3 to 3/5 of the Senate body in 1975). The aim was to stop Senators from giving long-winded speeches. In that way, they succeeded. But in doing so, they destroyed the Senate.

The filibuster’s one drawback is gone. The physical toll taken on someone who can’t stop speaking, not even for the bathroom, was enough to strike fear into the hearts of many prospective filibusterers. Now, all one has to do is file the intent to filibuster, or even threaten it informally over Twitter or email, and they get the desired effect. No consequences; no stakes. It essentially drapes a 60 vote requirement over the passage of any bill, a Senator can simply threat a filibuster and halt all progress – and who’s going to stop them?

This system dooms any bill that doesn’t have bipartisan support. If a bill doesn’t appeal to at least 60 Senators, all of the majority plus some of the minority, then it simply can’t be passed. Ironically, a tool currently championed by Republicans as a bastion of open debate and discussion is being persistently used by them to achieve the exact opposite. If they don’t like a bill, they can silently banish it to the abyss of the Senate agenda, where it is left pending on the floor until the 60 vote requirement materializes to save it.

Our parties don’t trust each other, not even slightly. The filibuster has provided them the ability to be loyal to a fault. They don’t have to argue to support their opposing perspective, they don’t have to listen to what the bill’s proponents have to say. Anything that the other side does is instantly blocked: there is no discussion about it. If the filibuster hasn’t caused party division, then it has surely aggravated it.

The filibuster, more than ever, wastes time. It wastes our votes, it wastes our money, and it allows institutional discontent to fester instead of being addressed. As pressing as the current fight for voting rights expansion is, the very thing standing in the way of its passage is what reveals its futility. If our legislators are undermined, and nothing can be accomplished, then our vote is undermined.

Restore our democracy. End the filibuster.